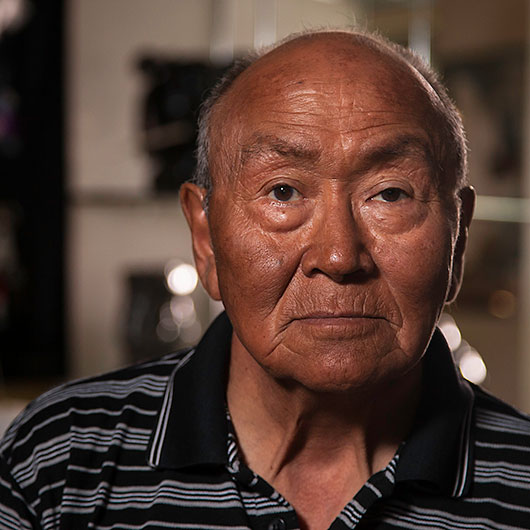

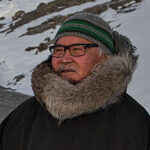

My name is Bobby Barron. I’m from the big river and now l live in Kangiqsualujjuaq. I was born in a tent by the bottom lake. When I was born, there were no professional services available; no medical services, no police, and there was no school. We still lived in camps like they did in the old days. I was born in a tent near the big river on December twenty-seventh in 1946.

I remember that as a child growing up there were no white people living amongst us. I grew up near the big river and spent all my childhood there. The Hudson’s Bay Company was based in Kangiqsualujjuaq, not here, and my childhood memories began there because my father wasn’t working so he was always out hunting; always hunting for food so we wouldn’t go hungry. They camped where there was wildlife to hunt. That was how our family and relatives lived. There weren’t many of us, but we all lived in one camp where we were happy and I remember that as a child.

As a child, I didn’t know anything that came from the white people because there was no work then. We chose to live where we wanted to live, and our diet consisted of wildlife that we harvested, such as caribou, mammals, and fish, which were important to our survival.

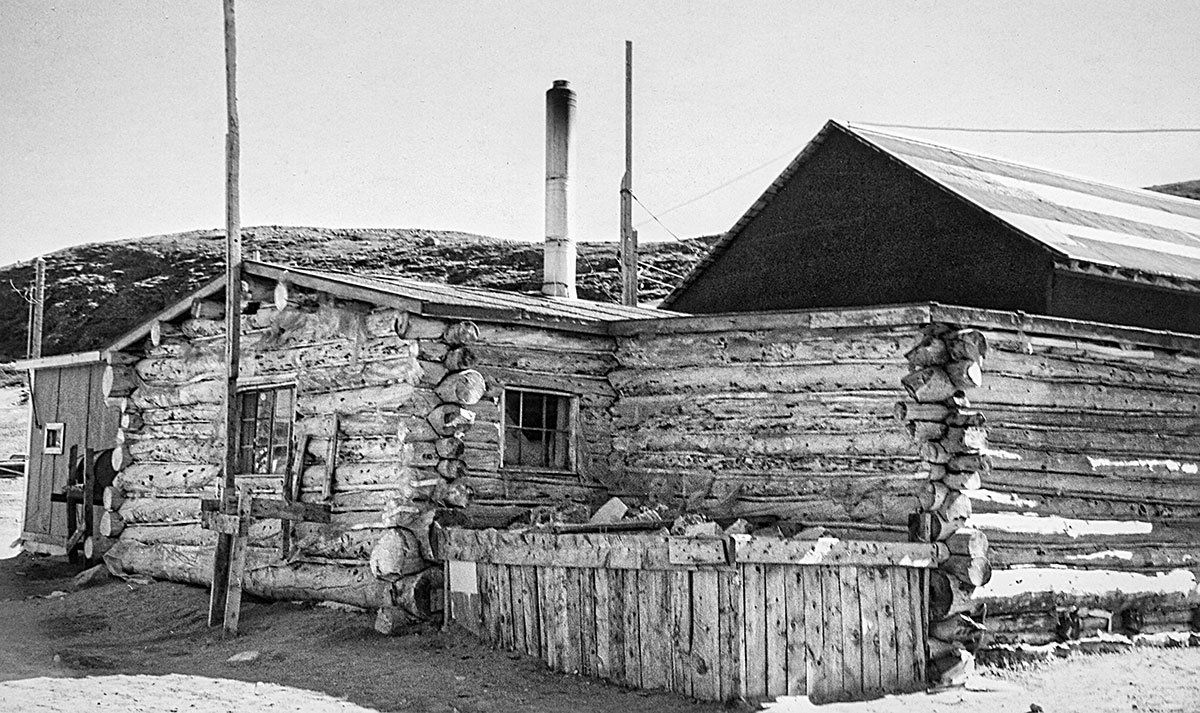

In Kangiqsulujjuaq, we used the wood from our logging to build the first co-op. When we got down to the big river, there was already a place set up for them but the logs couldn’t be kept in salt water too long so they were put elsewhere, and Willie Maria, along with some crew members were tugged by a tugboat while we took care of the logs and put them ashore at Akilisakallak.

The first ship that was there carried a freight of nets and two small boats that were the first capital items purchased with start-up funds of two hundred and fifty thousand.

Show More

The hardships didn’t cause any worry or have any effect on the Inuit because they continued to help and support each other. As a result, the co-op began to thrive.

Show Less

It wasn’t all smooth sailing in the beginning. Inuit were reluctant because they were Anglicans, thinking the Roman Catholic priest was tricking them into converting. And hearing their parents talking against us, our peers chanted: “Antichrist, antichrist!” That’s what I heard when I was visiting, because my father was involved with the Co-op.

My father used to say that when the Hudson Bay Company was the only one, we were not respected. Only if and when the trader felt like it would the store be opened up. He wasn’t at all cold, and our people were kept outside, waiting. What impressed me most was a question that was asked of Father Steinman by the Roman Catholic church: “What are you doing? You’re supposed to be converting Inuit, but have you just been helping them to make money instead?” He said: “Let’s worry about their stomachs first. Then later, when they are no longer hungry, I’ll convert them.”

And no wonder. Puvirnituq people were in a state of great hardship at the time when Father Steinman and Peter Murdoch arrived. They had to go a great distance to hunt and to set their fox traps. Given those conditions, it was no wonder that many were sent South, in a bad way due to sickness, to tuberculosis. They were too ill to keep the interiors of their iglus or tents clean. And so we began to move away from all that hardship through carving, when James Houston taught us, the people of Inukjuak, those who would become Puvirnituq people, and Qikiqtagaq people too, that soapstone could be turned into carvings that could be turned into money. That is really something to honour, thinking back on it. They would no longer only be working with fox pelts and sealskins, but able to generate money with their hands and their artistic talent.

They have been of great assistance to us, Father Steinman, Peter Murdoch and James Houston. Their names may not be mentioned all the time, but they let the world know that we could create objects of beauty with our hands in stone.”

“In Whapmagoostui-Kuujjuarapik, before the Co-op store began its operations, the population became aware of the deficiencies of the Hudson’s Bay Company. That is when they decided to start a store that could benefit both communities. The first Co-op was owned and operated by the Inuit. The structure was a mere 10′ x 12′ in dimension, compared to the size of it today.

About five years later the Cree planned to have their own store. It flourished during the initial years of operation but the Inuit Co-op began to struggle. Six of us founded the store, but I am the only surviving member. The year we began operation, two members contributed a lot by investing the fur they harvested. Those members were Elijah Kawapit and William Kawapit.

We six members invested $150. each, totalling $900. The community Catholic Priest took our money and returned with a $10,000.00 startup grant from the government. We were overwhelmed as we invited members to pay a $5.00 membership fee. Two years later, the Inuit Co-op began struggling so we decided to amalgamate the two Co-ops. That is the store you see today.”

This is what I thought about the mistreatment of my grandfather at the hands of a Hudson’s Bay Company clerk. I know how long ago it was, what was done to my grandfather, and I know the name of the one who did this act, where he lives, whether he has children and grandchildren who I could potentially treat the same way. These things could happen to Inuit, and they happened just like that.

This is what I thought about the mistreatment of my grandfather at the hands of a Hudson’s Bay Company clerk. I know how long ago it was, what was done to my grandfather, and I know the name of the one who did this act, where he lives, whether he has children and grandchildren who I could potentially treat the same way. These things could happen to Inuit, and they happened just like that.

It hurt me deeply to hear this, but it’s better now, isn’t it? I think the outcome is for the better, now, so long after what was done to my grandfather. His son—my father—was moved to help the co-operatives when they were being established in Puvirnituq.

My father was away from home for three years. I was a small child when he spent three years in the sanitorium for tuberculosis, 1953 to 1956. There, it seems he learned a bit about working with numbers, what Qallunaat call simple arithmetic. And because he was among the Qallunaat, he started to learn a little of their language. When I was a boy, he interpreted for people everywhere, so I used to think he was really proficient in English. As it turns out, he only knew a few words here and there, but he put this ability to the service of the people when the co-operative was getting started, around 1959 and 1960.

This has become something I am thankful for, looking back on it, as it led to a better life for Inuit and for our family. My father helped greatly in the establishment of the Puvirnituq co-operative, and in its growth.

“My father let Inuit go hungry, and I do not wish to take his name. That’s what I told them, and it is still not my name. I am not a Goodyear, and have never wanted to be. My father would allow Inuit to go hungry, with all that merchandise sitting inside the Hudson’s Bay Company storehouse while they were desperate. Because Inuit had no money, he should have shared some it, but he gave away nothing. That’s how my father was—a Company man.”

“The sale of carvings started through the Hudson’s Bay Company which was the only buyer and this was the source of survival for the Inuit. After a while the Hudson’s Bay Company no longer wanted the carvings and I remember people struggling to figure out how they would survive.

After carving sales were stopped the Co-op came into existence. The sale of carvings was a big business here when the Co-op was first created in the early 1960s. But because there was no money to purchase our carvings we would donate five dollars of our own money so that the carving business could be started up again. We donated all we had in order to create a pool of money to purchase our carvings

That was the only source of funds we had but we kept running out when we were trying to start off the Co-op. I would also like to express my deep appreciation to the people of Puvirnituq, who helped Inukjuak buy the carvings by donating two thousand dollars.”

They all come together in the federation. The co-ops of Nunavik, any of them, can experience a hard year, feeling great financial strain and almost collapsing, but others are more stable. So they are all able to help one another, right up to today, and fifty years later, not even one co-op has ever been allowed to collapse!

“At FCNQ we were finding that the Kuujjuaraapik Co-op was taking a long time to get on its feet, and because of this situation, I went back on the community radio to tell them: “Let’s go! I will help you Inuit, because you need a new co-op. And because I’m going to help, I want some help from you.” Their debts were way too high, so I challenged them to lower their debts. To my surprise, the same summer, they got their new co-op! I really made that happen.

I can do something, when I really grab a hold of it. And all the while, my kids, fending for themselves—and my man, when we were both looking after sealift, on the airport runway we’d exchange “Hi” and “Bye” in passing. I was completely astounded, one time in Akulivik, when I looked out the window to see a ship, so close, and Elijah was aboard! He was to sail that same evening. That’s when I was working with the co-op there. Even though it was a stressful time, those things were really enjoyable.”

Lucy Grey

Lucy GreyNo-one, whether they’re poor, or starving, will have our backs turned on them. Inuit are going to band together, because it’s our way. There are the powerful, who are better providers, and those who cannot provide as well, but just because they cannot provide as well, we will not turn our backs on them. When they are starving, we will not just stare at them, because it is in us to work together. So the Federation and the co-operatives have core Inuit principles at their foundation, and because of that foundation, they are useful to us.

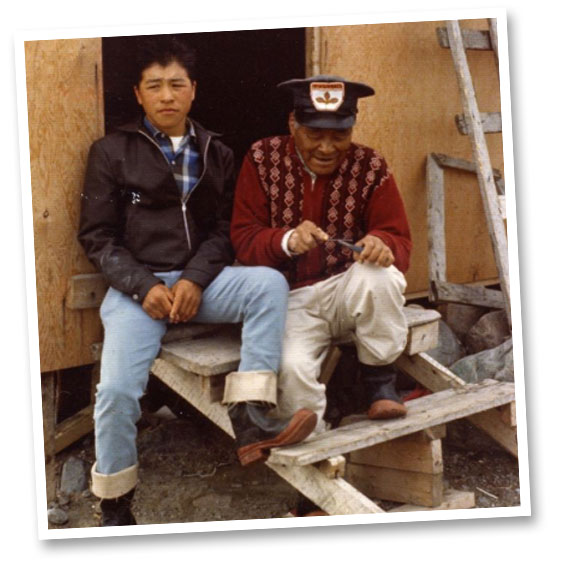

Elijah Grey

Elijah Grey“It’s no wonder that some Inuit did not immediately agree with the James Bay Agreement—they knew this well from being part of the co-op movement. They didn’t want the government telling them, “Do it this way!”

It seemed the government spoke like the Hudson Bay Company, “You’re going to do it our way!”—but the co-ops had a different way of reaching consensus. The ones who had grown the co-operatives had strong minds.”

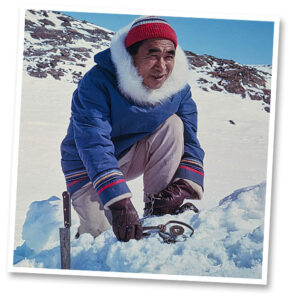

Peter Qumaluk “Peter Boy” Ittukallak

Peter Qumaluk “Peter Boy” Ittukallak“I have been a carver for a long time now. I was four years old the first time my grandfather gave me a little piece of stone and said: ‘make this.’ I would practice on it and try to make sense of it and that’s how you learn how to make one. When I was 5 years old I made one myself, and that was the second time. I was 7 or 8 when my grandfather died. Then the only way was to try on my own. I would watch my father, my uncles and would follow their examples and that’s how I had gained my skills.”

“Our Co-op here is 57 years old. For 30 years I was President. I am still a board member. It is a pleasure to take on these opportunities.”

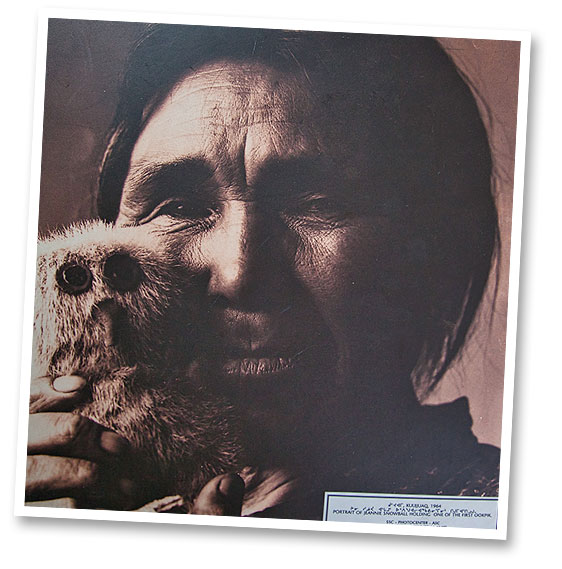

Bobby “Snowball” Aputiarjuk

Bobby “Snowball” AputiarjukMaybe it will be better to start my story about our hunting days, seeking animals. That is when the government started introducing different ways of making unique, not too expensive salable products.

We were encouraged to create products based on our personal life experiences as Inuit. Soapstone was imported for the men to use, and women were encouraged to produce sewn crafts. Money would come our way from sales. For about a year we were out on the land seeking caribou. I remember being alone with my mother on the qamutik of a dogteam while my older brother was elsewhere hunting. We were in three dogteams, my uncle with his wife as well as a father and son team originally from Kuujjuaq. As we were travelling, very unexpectedly, a plane flew over to us. It was a lucky thing, considering we were about to get into the trees, where the plane would never have seen us. They were surprised to learn that the sewn craft they were inquiring about already had a name: “Ookpik.” An Ookpik that fed my mother’s family. When my mother was still a girl she made that owl remembering her life experiences. An owl with big eyes and a catchy name is what attracted the consumers. They weren’t sure who had created this craft, so two women, my mom and my aunt, ended up getting in the plane and taking off from the frozen lake. Left behind, we continued to travel to Kuujjuaq.

Later my Mom (Jeannie Snowball) and I were invited South by an American who apparently worked in Education making visuals and educational materials for children. Shortly after my we were invited to attend the newly forming Ilagiisak (Federation of Northern Quebec Co-ops). It is there that my mother received all kinds of gifts to give to our community, donated by children. That is how it was, at a time when our way of life was being discovered through such creations.

Show More

The men would go seal hunting to get skins for the Ookpik dolls while their women worked very hard at producing the Dolls so that the men would have money.

Many types of Ookpiks were made at the time when it was just being discovered and in popular demand. And many of our women worked in teams to mass-produce the various parts of the doll: the feet, the base, some made the beaks while others made the eyes. All together, using a sewing machine, a total of 500 were made each day.

Show Less

“I used to just work for the Kuukjuaq co-op store, then I ran for the board of directors, and then I had the co-op president’s position.

“The Kuukjuaq Co-op did not make a profit—it went bankrupt for many years—but now we are no longer in danger. The previous store manager, Sandy Saunders, used to state that he wanted to hide under the table considering the situation the store was in, whenever there were financial statements to be read. But at present, we can stay seated at the table. Companies are networking with us, we have a gas station and we now run the cable business as a co-operative—our members are more interested in supporting our store as they understand more about how the co-operative works.

Show More

To my understanding the FCNQ is the foundation of all the associated cooperatives as if it was the mother, giving loans, helping with the economic development. Also, because all the co-op stores are running, the FCNQ is able to stand strong. And the Inuit members are persistent. This is what I am proud of, how hard Inuit work to keep this running.”

Show Less

My older brother was president of the board of directors. Before our meeting had started, I noticed him holding a bible. As we settled into our seats, he announced that he would read from the bible that morning.

We had a great challenge. We were not able to see what could be accomplished or where we would go, and unable to answer the uncertainty.

From Old testament Isiah 42 verse 16, this is what he read that day: “I will lead the blind by ways they have not known, along unfamiliar paths I will guide them; I will turn the darkness into light before them and make the rough places smooth. These are the things I will do; I will not forsake them.”

The word of God is flexible in a way that even if we reread the same verse it can still be a revelation in other areas in life that we find challenging, it is not narrowed to the purpose of independent stores. Back then, when stepping into the unknown of running something, it made us rise up and gave us strength.”